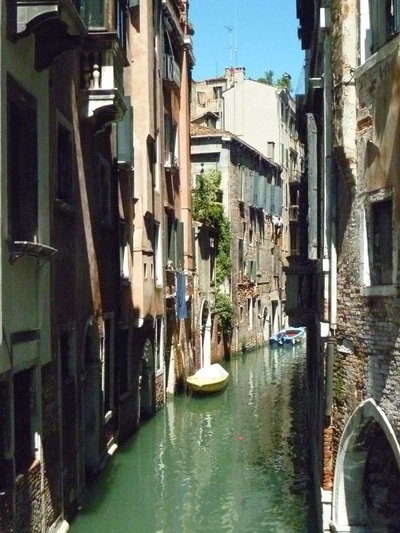

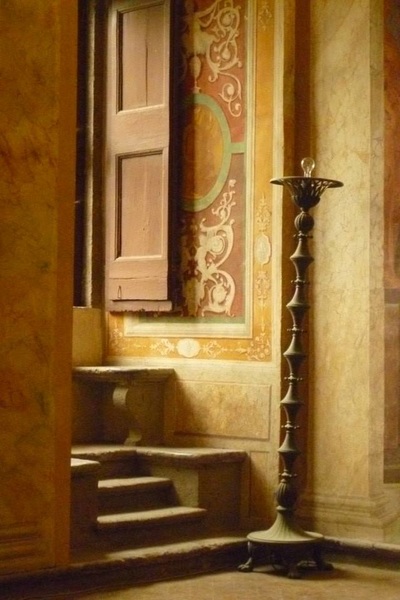

I’ve always been fascinated by buildings; one of the first careers I was aware of – at the age of 10 – was ‘architect’ and I spent entire months at that age and for a couple more designing houses and indeed entire estates on graph paper. And as anyone who has read my blog posts knows, I often write about buildings. Other times I write about ‘historically important places,’ which can include buildings. And, I not infrequently write about the ruins of… yes you guessed it, buildings. So when I decided just a few months ago to enter a Graduate Certification Program in Historic Preservation in pursuit of a Grad Certificate, no one who knows me was surprised. One thing that came as a shock as I began the program and dutifully did my first readings was the realization that the intrinsic value of, and importance in, preserving buildings wasn’t an external, absolute truth that people and societies work toward upholding. (As if the current destruction of ancient monuments, cities and more in Syria wasn’t enough of a clue.) In other words, apparently what I have all my life understood to be an underlying principle of how one looks at the world is not a natural perspective. It was only in the last few hundred years that people began to look around and see that the built – and natural – environment was important. For whatever reasons, ranging from the rate of change to the power of the individual in various societies to the normative belief structure in any given moment in time, the idea of keeping ‘old stuff’ from disappearing, deteriorating, falling down, or being demolished was simply non-existent. In a way, I knew this already though its import hadn’t struck me to this extent. For instance, it is common knowledge to anyone who’s been on a guided tour of the Coliseum in Rome, or simply looked it up online or read a book about it, that the original structure was covered in marble which was ‘repurposed’ by later builders for new buildings. Or that the ancient site of Villa Adriana (Hadrian’s Villa) in Tivoli, outside Rome, was a kind of feeder site for the nearby Villa d’Este as it was built in the 16th century. Or that pretty much the entire country of Italy is built quite literally on forgotten structures that emerge like ghosts of long-forgotten cities when somebody digs a hole in a basement. What makes this all so fascinating to me – the non-normative, culturally-based concept of preservation as a value, I mean – is trying to figure out where I learned it. Was it my mother’s fascination with Native American pot shards, arrow and axe heads, and hand-woven blankets? Was it an extension of my perhaps compulsive need to document in writing the ups and downs of my life… if it’s not in stone, it didn’t happen? (Even that impulse though is secondary; one has to believe, first, that past events matter at all to the present, or the future, in order to make sense of documenting them.) Is it something having to do with identity, the idea that we are, as are cities and countries, made up of, identifiable by, the sum of all events, ideas, concepts, and cultural artifacts – buildings among them – that we create? Or was my belief that there is intrinsic value in the past, and in objects, places, structures that somehow represent that past, sparked by some event? I don’t remember a time when I didn’t think ancient Roman ruins or abandoned Southwestern ghost towns or the battlefield of Culloden in Scotland or the Acropolis in Athens were important in their own right. But perhaps somewhere, hidden in the shadows that make up my childhood, was a moment… something said in passing… a word whispered to me at night… a disembodied voice from the past that told me that history and time and moments within both can be read through the blocks and beams and burial sites of people who have come and gone. And that someday, we too will be gone, leaving our own versions of ourselves for others to preserve… to read our lives in what we leave behind. I like that thought.  Since the 11th century Italy’s prominence in the fashion world has been unrivaled, with names such as Giorgio Armani, Roberto Cavalli, Gucci, Dolce and Gabbana, Ferragamo, Versace, Prada demanding our attention and our dollars. And the cities most often associated with fashion in Italy are typically Milan and Rome. So imagine my excitement when, on a visit in 2011 I found a fashion exhibit in the center of Venice, of 18th and 19th century dresses on display at the Palazzo Mocenigo. The palazzo is itself a work of art, its origins Gothic and pre-17th century. The family Mocenigo were wealthy and important, and seven of them became doges – essentially dukes – of Venice between 1414 and 1778. In 2013 it was expanded and renovated, and it consists of more than 20 rooms on the first floor alone, each of them imbued with a sense of wonder and a certain quality of surreality, not unlike other Italian spaces in which history is both yesterday and right now. Today the rooms have a newness to them that in an odd way blends and makes more present that sense of the past, and its collections ranging from clothing to perfume to paintings and sculptures and chandeliers, from glassware to tapestries to fans and photography depending on the season and the choice of the curators. In 2011 the palazzo was just being renovated, and even so we were allowed to wander in, to experience the immersion in color and texture that was the exhibit showcasing clothing from Russia with more than 200 works, and they were astounding. I wandered the small rooms in which they were displayed and so taken was I by the silks and beads and draped sleeves and pleated skirts that I did not venture into the rest of the museum. The colors were muted, somehow, but not without a texture and a softness that begged for a touch, and in their very presence made me wish I could slip into one, walk the marble floors with the hem just whispering against the floor. I could almost feel the silk against my skin. (Each exhibit will be different, and like any museum it will shift and change throughout the years. No matter the displays, this is one museum you should make it a point to visit. For more information about the above-mentioned exhibit, see here.) (Address: Palazzo Mocenigo, Santa Croce 1992, 30135 Venezia)

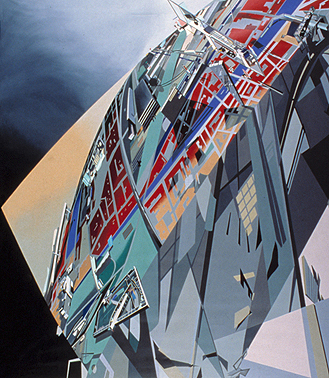

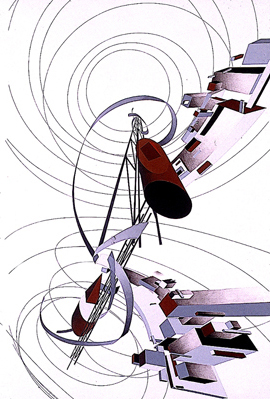

I’d visited the Roman Forum a number of times before, starting before the city of Rome fenced it in and began charging visitors to walk the same stones that Cleopatra and Marc Antony walked, to gaze on the steps of the Senate where Julius Caesar died, to stand beneath the ruins of the Temple of Saturn and marvel at its unimaginable former splendor. When they started charging, I visited less, but who needs to walk those ancient stones every morning on the way to coffee anyway? Once or twice a week was enough. So while I can’t say I knew the Forum inside and out, I knew it well enough to know that the mosaic I glimpsed on the ceiling of a church I had barely noticed before, was new. Well, not new new. Nothing in Rome really is, and especially not in the very heart of it. But new to my eyes. My heart stopped as my feet did, and I searched frantically for a way in to the church, or temple, before me. It’s bronze doors did not yield, it’s hexagonal design defied my attempts at finding another entrance, and finally I had to conclude that there was no way in. At least, not from the ground level. (I later learned that these doors are kept locked, they can be opened with a key – the original key that locked those doors for the first time in the 4th century. A 1700 year old key in a 1700 year old lock.) I left, determined to find my way in. I didn’t – not that year. But the following summer I returned, knowing some things. For instance, that it’s the oldest church in the Roman Forum, originally created in 527 by Pope Felix. I say created, not built, because the structure was there and Pope Felix added an apse mosaic – the one that had caught my eye, in fact – and some basic church-ey furnishings. And that this act of changing a temple into a church signaled the fact that the Church was finally more powerful than the pagan beliefs that had until then dominated. I learned that its name is the Basilica of Santi Cosma e Damiano, and that these two men were twin brothers, physicians both, and that for centuries sick people came to the church to sleep within its walls in the belief that so doing would cure them of whatever they suffered from. And I learned that the entrance is outside of the Forum, from the Via dei Fori Imeperiali – the street that runs beside the Coliseum. So in I went, and like a pilgrim I walked straight to the part of the interior from which it is possible to stare open-mouthed, and I’m sure I did, at the mosaics that had by then haunted my dreams for a year. Masterpieces of 6th- and 7th-century Byzantine-style art, these mosaics show Christ’s second coming. Christ himself is in the center, with Saint Peter presenting Saint Cosmas and Saint Theodorus (right), and Saint Paul presenting Saint Damian and Pope Felix IV. The entire is brilliantly colored; blue and gold predominate, with reds and whites and greens as secondary hues. We are not so well versed in how to read the stories told to us on Church ceilings as people of the past have been. Sheep and the temples in Jerusalem and the four rivers of Paradise and clouds and scrolls and crowns and golden water and palm trees and phoenixes and thrones seem jumbled, and to my eyes become less about a perfect story than about sublime beauty. It’s hard to believe, and yet so perfectly apt – we’re in Rome, after all – that these vivid colors have survived 1400 + years, that the story they tell is one that still gets told, and that the dome and the heavens are somehow not actually the same thing.  On the island of Bisentina in the lake of Bolsena, northern Lazio, Italy, is a church. Actually there are seven churches on this island, but only one of them matters to me. And I can’t stop thinking of it because I’ve never seen it up close. I’ve sailed around it often and from the deck of a boat, the structure is half-hidden by vegetation, visible only in parts. Vines climb the walls, and its dome emerges from the trees, a large, leaning cross on its top. These glimpses jolt me with a sense of desire so strong I can only liken it to the emotion that drew me to Italy in the first place. I’ve written about that emotion (here), and this church causes the same sensation that is made up of equal parts fear, need, loss and a strange nostalgia for something I have never touched – perhaps indeed because it is unattainable, unreachable, untouchable. It’s not for lack of trying. The church, and the other structures on the island, and in fact the island itself, are privately owned and while at one time not long ago it was possible to visit by hopping on a ferry or joining a group who were planning to picnic, sometime in the last ten years the owners of the place shut down that possibility. Rumor has it that a part of one of the churches – perhaps this one that I dream of – fell near an unsuspecting tourist, almost causing great physical harm and resulting in a complete shutdown of anyone else’s visitation rights. It seems somewhat uncharitable that I would blame that tourist for my never having set foot on the island, but I do nonetheless. Some quick history. The island is the larger of two in the middle of Lago Bolsena, a volcanic lake in northern Lazio. From the 9th century the island was a haven for people escaping ‘barbarians,’ and has passed in the centuries since through the hands of popes and rich families (often the same groups), who used it for summer vacations, hunting, and idyllic getaways. Because no one is allowed there today, the island maintains a large diversity of plant and animal life. It is currently (as much as can be discerned online) owned by Princess Angelica of the Dragon, but as far as I can tell she is a mythical creature, hardly seen or heard of. The church that haunts my desires, one of seven on the island, is called the Church of Saints James and Christopher. It was built in the 16th Century by the Farnese family, friends of popes. It is in the shape of a cross, as was typical. The dome is of iron, and often attributed to Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola – one of the three most famous Renaissance architects. He worked with Michelangelo, and had a part in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, but while it would be nice to think he created this dome on the church of my dreams, he was dead by the time it was built. As mentioned, its walls are covered with vines and flowers, and the whole is juxtaposed with beautifully kept gardens; the Princess employs a veritable fleet of gardeners to maintain the grounds for no one. Inside, by all accounts, are frescoes as beautiful as any 500 year old frescoes can be, neither more nor less amazing than any other church. This should be a comfort really, and take some of the sting out of my inability to see them. And of course Italy is full of ancient churches, far more than I’ll ever be able to see up close. None of this helps, and my desire only grows. I’m not sure why this one pulls at me the way it does, or what I hope to find when I finally am able to walk on its manicured lawns, enter the shadow of its ancient doorways, walk on its marble floors and drink in the frescoes painted by long-ago hands. But I trust this inner knowledge that it’s worth the attempt. And oh yeah, the entire island is guarded by a stone lion. That must mean something.  MAXXI Museum, outside, dusk MAXXI Museum, outside, dusk I first became aware of Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid when my not-yet-husband and I visited New York in 2006. We went to the Guggenheim Museum, and halfway down the spiral we ran smack into an exhibit that halted me in my tracks. Made up of drawings and paintings and furniture and models and objects that defied classification, each piece of Hadid’s work seemed to shift from building design to creature to art to fantasy, and I was entranced. It was like walking into someone else’s dream of the future. I became slightly obsessed with Hadid and her work, did a lot of research online, followed her career – a most amazing career that includes being the first woman to be awarded the distinguished Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2004, founding Zaha Hadid Architects in London (currently working on 950 projects in 44 countries), and designing some of the world’s most unusual structures – and was delighted when I found out that it was she and her firm that was brought in to design the MAXXI in Rome. MAXXI – the Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, or National Museum of the 21st Century Arts - was completed in 2010, and consists of two museums, one for art and one for architecture, an auditorium, a library and media library, a bookstore, cafeteria, bar, galleries for traveling exhibits, performances and educational activities, and a large outdoor square for art works and live events. Details like the above are nice and all, but what really makes Hadid’s MAXXI the “masterpiece fit to sit alongside Rome’s ancient wonders” is more than its function. As all her work is, the museum is a breathtaking structure designed specifically for its context – a looping, swooping, light-filled series of halls and slopes that feels both solid and ethereal. It is filled with bronze creatures and series of flowers in oils or acrylics, architectural models and fashion exhibits, posters and photos, documents and journals… truly the list is endless. Around each new sweep of white corridor lies another wonder, and you cannot help but be drawn onward, upward, and into some kind of otherworldly sensation. The entire experience echoes and almost feels like a journey to the original ancient city might have, despite or maybe because of the museum’s futuristic design and contemporary art. The MAXXI has become part of what Rome has always been: a world of wonders created by people who are larger than life, who put their stamp on history with a structure that endures for ages and engenders wonder and amazement in us all. Don’t miss it on your next trip to Rome!  Hall of Mirrors, Doria Pamphilj Hall of Mirrors, Doria Pamphilj #1) Palazzo Doria Pamphilj – in the Featured Museums series. I love museums. Even so, I avoided them in Rome for a long time, preferring to spend my days wandering through the open air, many square mile museum that is the city’s Centro Storico (historical center). Then one day instead of walking past the entrance do the Galleria Doria Pamphilj which really looks more like an entry to a courtyard, I went inside. And my world expanded. Museums can be daunting; this one is not. It is enchantingly small – for a museum… for a palace. The entrance leads you into a courtyard through hallways, up stairs, and finally into the museum proper – which is actually just a section of the home that has been opened to the public. The palazzo itself was built in the fifteenth century and was home to a number of famous Italian families before falling, by marriage, into the hands of the Pamphilj family who own it today. Through the centuries it was expanded, with each family adding rooms and entire wings in the style of the day; it is now the largest private residence in the center of Rome. In the early 1600s, Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini began collecting paintings and from this relatively small endeavor grew what has become quite a stupendous collection that includes original works of Caravaggio, Velazquez, Filippo Lippi, Annibale Carracci, and many more. Ceilings are 20 feet high, walls are deep, blood red, or gold or blue, some covered so thoroughly with paintings that they look like wallpaper themselves. Each room features a different kind of art: landscape painting, biblical figures, portraits, a mixture… there are brocade wall hangings, 16th century armchairs, and an original wooden floor. The hall of mirrors, I am told, is just like a mini Versailles, and lined with sculpture from ancient to Renaissance. Just off the main area is another, dedicated room for sculptures, and a marble bath set on a marble floor… and it goes on and on. But, not forever. You can easily see everything in the museum in less than two hours – more quickly if you hurry. But you won’t want to. Each piece of art, hand chosen by a family member to adorn the walls, to be part of lived space, is meaningful in a way that most museums never manage. For this is not just a museum, a place for random strangers to wander and become lost; this is a space of family, of memory, of beauty chosen for the way it made someone feel. Sharing its wonders is, for those of us who take two hours to look more deeply, just a little bit like touching that beauty for ourselves, and feeling the echoes of centuries. Don’t miss the experience. by Teresa Cutler-Broyles On my first visit to Rome, just off the plane, I spent an hour taking pictures of the Coliseum. I walked the Roman Forum in awe that my feet were treading the very same ground that Caesar had walked, and stood inside the Senate building where he met his death; I imagined the screams, the blood, the import of that moment, and I could not shrug off the feeling that somehow even the ground held memories of both. I stood under the Triumphal Arches of Septimius Severus, Titus, and Augustus and – because the iron fences had not yet been erected – touched the marble that I imagined had been touched by hundreds of thousands of people in the years since they were new and glittery in the sun. This entire area was just as I had always imagined it would be – serene despite the crowds, quiet and respectful, as it should be. Soon, I left the Forum area, determined to see Piazza Navona, a place that had existed as a beacon in my mind for years. I set off through the streets. It was close, according to the map. My anticipation grew. Any moment, I’d be there where I’d see fountains by Bernini… a church that holds the bones of a 4th century saint… an Egyptian obelisk from even more ancient Egypt… echoes of chariot races and boat exhibitions… the Pamphili palace…. In essence it was, in my mind, as much hallowed ground as the Roman Forum. I got closer – just around the next building and I’d be surrounded by another space filled with past glories…. Perhaps it was because I had by then been up for more than 24 hours. Perhaps it was because I had forgotten to eat and so was likely quite low in blood sugar. Or perhaps it was that finally reality hit. In any case, this was the revelatory moment: I rounded the corner and was assaulted by noise, then chaotic movement. I felt outrage first, then fear, and then a sinking sensation akin to betrayal. Children ran and screamed, chasing balloons and bubbles. They climbed on benches and iron fences erected to keep people off the statues, and they shrieked as they ducked away from parents who, in truth, seemed more interested in taking photos or looking at the hundreds of street vendors’ products. My heart sank even more as I walked in a terrible haze across the cobbled street onto the main open piazza and through the lines of oil paints, water colors, photographs, caricatures, trinkets, cheap souvenirs. What right did they have to be there? Why did the city allow this – a flea market in an ancient site? And what of the restaurants lining the edges of the piazza with chairs and canopies that extended almost halfway into the streets on all sides? Tourists sat and talked loudly in a variety of languages. They ate and took photos and laughed at each other. Waiters accosted me, everyone, telling us why their place was better than all the others. People on bicycles wove through the masses, ringing their bells, stopping and starting to miss the people who couldn’t seem to pay attention to anything other than their own wonder. Everything was too loud, too noisy, too colorful. Too disrespectful. I sat down abruptly on a wide concrete post, almost in tears. I had learned in my three years of archaeology classes that ancient sites should be protected, that they shouldn’t be desecrated by such crass endeavors as bubbles blown from plastic bubble guns, shouldn’t be subjected to screaming children who didn’t even notice the 400 year old fountains, the thousands of years-old obelisk. And they certainly shouldn’t have a flea market going on right in the middle of them. I sat there for a long time, miserable. Illusions shattered. Rome was nothing more than a carnival, a circus where people came to buy and sell, scream and yell. It was a pretender, an imposter, not an ancient, venerable site at all but a modern day mess. I ate a breakfast bar, dejected, ready to return to my hotel, and then slowly – perhaps nutrition hitting my bloodstream? – had what I have come to believe is one of the most important realizations a traveler to Rome must have, one that certainly seems to go without saying. Except I hadn’t known it until that moment. Rome is a living city. It is not frozen in time, to be viewed and marveled at. It is ancient, yes, and it is also modern. It is filled with first century buildings and original tile, and 21st century people living lives that involve smart phones and Manolo Blahnik shoes and plastic bubble guns. In any given skyline of the Centro Storico (Historical Center) one can see 2000 or more years of churches, temples, spires and sculpture. And at any given time a visitor can move from the present to the past in an easy couple of steps. For most of its life Rome has been what it is today: a city upon which people from all corners of the globe have descended; a city that merges its history with its present, almost seamlessly creating a site of wonder and grit; a city filled with the ghosts of the past and the realities of the present; a city in which flea markets have peppered the piazzas for centuries and generations of people have bartered for a trinket, a souvenir, a picture; a city in which present-day artists chose as their subjects the intrusions of its past. It is loud and dirty, and filled with glittery marble and crumbling walls. And finally, it is a city in which screaming children become the voice of the future. Humbled, I found my way back to my hotel that day, slept for 10 hours, and the next morning I entered the Rome that is, instead of the Rome I was expecting. And it is, as it will be a hundred years from now, more than can be dreamt of. (Photo credits to tripomatic, online.)

My Writing Process Bog Tour

A big thank you to Linda Lappin who invited me to participate in this Tour. Her wonderful historical books contain vivid characters and deeply significant places as she leads readers into worlds that feel, always, a bit haunted by those who have gone before. I have been asked to answer four questions. 1) What am I working on? I'm always working on a number of things; lately I'm doing both fiction and academic writing. This blog post will leave the academic writing for another time, and will talk about my Historical Fiction and Young Adult novels. We'll start with YA. YA: Currently I’m working on Book 2 in a YA series of three novels. The first book, titled One Eyed Jack (available on Amazon), introduced young readers to Lauren and her one-eyed horse Jack. Book 2 takes place a year later as Lauren and Jack spend a summer on an adventure ranch in Colorado. Book 3 will take place a year after that, on a ranch in Texas where they learn to herd sheep and goats. Historical Fiction: After finishing Monsters Fall, my time travel historical novel set in 1570 Italy, set in the garden of Bomarzo, I recently bgan working on another time-travel historical novel, this time set in Shakespeare’s England. Shakespeare himself plays less of a role than his work does, and I expect to be done with this one by spring, 2016. 2) How does my work differ from others of its genre? My YA novels – ostensibly ‘girl and her horse’ stories – differ significantly in that they deal with challenges faced by a horse with a significant disability, and by an owner of such a horse. Many YA novels offer models of relationships between young people, male and female, and explore the fears and insecurities that accompany negotiating those relationships – and mine do that as well. But the added element of having a one-eyed horse weights those other issues in significant ways. Historical Fiction: My historical novels differ in that they add an element of time travel – a kind of science fiction spice – to a foundation of historical fiction. Not only do my characters from today encounter and interact with historical figures but they experience life in the past as only a present-day person could. We get not only details about life in the past but the discomforts and joys, dangers and revelations that could occur from an ‘outsider’ perspective. These books have two main characters, one from the past and one from the present, and their stories entwine in ways that neither character – nor readers – could have imagined. 3) Why do I write what I do? Everything stems from personal experience, one way or another, though my books are not necessarily autobiographical. With one exception, the YA series. YA: Twenty years ago I was asked to assist as a veterinarian took out the eye of a horse I’d known and worked with. The event connected us in a way I hadn’t been connected to any other horse; I purchased him a few months later, and he and I became an inseparable unit. We went everywhere a ‘normal’ horse could go, he learned to jump, and he became one of the best horses I’ve ever had – before or since. I felt writing about him would honor his memory, let me talk about him in ways that would entertain others, and would introduce the possibility that simply losing an eye need not be a tragedy. Overcoming adversity is easy with love, and lots of courage; this is a message I feel is important to convey to young adults. This process is much more planned and organized - and more personal - than that of my other work. Historical Fiction: My historical novels stem from an entirely different source. They always begin during a visit to a place – sometimes a place I’ve visited before, but more often somewhere new to me – that has some kind of historical weight. Examples of this would be: Shakespeare’s Globe Theater in London, the Imperial Forum in Rome, the underground Vaults that run beneath the city of Edinburgh, or – as with my novel Monsters Fall mentioned above – a 16th century Mannerist garden in Bomarzo, Italy. The story begins as a… sensation. A sense that somehow I have slipped… and I can almost hear, almost see people who have been there before me. It’s not as metaphysical as feeling as if I’ve found a window through time; it’s more an overwhelming realization that I am walking in the footsteps of hundreds or thousands (or millions, in the case of Rome) of others, and that a myriad of stories have played out right there. It’s as if those places are a book of sorts, and that ‘reading’ that book will bring forth the lives of those (imagined) others. At that point there isn’t yet a story, there is only the sense of something lurking in the back of my mind, a moment or a whisper I didn’t quite hear. For a while – a week, a month, a year – I often feel as though an idea, a memory, a thought, has slipped just past my line of sight and lodged itself into a kind of ever-growing place somewhere in my mind that will, when it’s ready, begin to coalesce into a story. I learn who my main characters are and I know the ending, but no more. And then… 4) How does your writing process work? Historical Fiction: After all of the above… one day I just sit down and start writing. It is as simple as that, really. I don’t outline, but by the time I start putting words to paper I know who my main characters are, I know where they meet, I know their goals and desires, and I know the end to which they are all moving. As I begin writing – via computer – I also buy a new notebook which becomes the place where all the stored up ideas, thoughts, bits of conversation, connections, possibilities end up – written by hand. I write down everything that comes to me at this point, and I’m meticulous about especially keeping track of questions I have about the true facts of history as well as the interweaving of the stories within my novel. I run through possible story tangents, I ask questions about characters’ motives, and I often ask, in fact, who the heck that person is who just appeared. For you see, as the story itself unfolds I find that my characters, more often than not, do or say things I didn’t expect – or that a new character arrives on scene unannounced and unplanned. These are my favorite moments, and it is here that the story begins to tell itself. For me this is the most exciting part of writing – the reality that the mix of weighted, historical place, real historical figures, a present-day character who travels to a foreign land, and the magic that is writing and storytelling itself, is far larger than I, and far more independent of me than it, perhaps, should be. I stop writing when the story ends, and the ending is always the ending I knew it would be from the beginning; how the characters arrive there is neither clear to, nor dictated by, me. It’s an exciting process, and when I finish a novel like this it always exhausts me. Next week the authors you’ll be hearing from include Naomi Sandweiss, a writer of history and creator of worlds that weave historical figures into today’s reality. Two other authors will be posted by the end of the day GMT, January 28, 2014! Returning is such sweet sorrow....

Each time I go to Italy it feels more like home. This has both good and bad elements, and the most confusing is that moment when I step off the plane onto my actual home soil. I have in my heart and in my Facebook photo albums images and memories - proof, if you will - that I actually was far from my everyday life. And yet, somehow, it feels as if I've not quite left here, not quite returned, not quite - yet - begun to separate myself from either there or here. Along with jet-lag, this sense of returning/always been here/always there is rough to navigate. It lasts a week or more: fitful sleep; strange dreams in which I am drinking coffee on Borgo Pio, strolling along Via Vicenza to one of my favorite restaurants; boarding a vaporetto in Venice to be carried toward Hotel Centuaro. Coffee slowly begins to taste normal again, and hearing English everyday and translating it into my broken Italian becomes less and less frequent. Finally I wake at the right hour, and don't drift off to sleep at 3:00 in the afternoon. It is the first night's full sleep when I come fully to the realization that it is only in my dreams that I walk the cobblestone streets of Pitgliano or sail on Lago Bolsena, and that I am here, in this home instead. Both call to my heart, and for now I will talk and think and dream of Italy while I fill my days with the joys of walking the dogs and talking with my husband and coffee and dinners with friends. That way when I next go to Italy I can dream of these things, and keep the balance in this world in which I live, always, in two places at once. |

Teresa Cutler-Broyles

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed